Mobility from an athletic point of view

When we talk about Mobility it’s important we know exactly what we’re referring to. A very basic definition is; “the ability to move or be moved, freely and easily”. So when we think in terms of joint mobility, it’s the ability of that joint to pass through a complete range of motion without impairment. Physiotherapists often assess range of motion with both passive and active assessment, to observe possible limitations to movement from injury, biomechanical issues or sometimes just poor activation.

Mobility is important since being able to move through a full range of motion will ensure the ability to train the body to the fullest potential. ‘Mobility work’ is often associated with the preparation off the body for movement or exercise using a variety of tools like static & dynamic stretching, resistance bands, foam rollers and trigger point balls. Much of this type of prep work is about manipulating soft tissue to increase blood supply, reduce neurological tension and free up joints for movement.

Mobility, part of something greater…

When it comes to athletic performance and the requirement for movement to be skilful; i.e. controlled, precise and purposeful, being mobile isn’t enough, we need to be flexible. So what’s the difference? Flexibility is made up of the components of mobility with stability, or to put it another way, the ability to produce and control strength through range of motion. So while being mobile means you’re able to move a joint into a particular position or through a range, being flexible is the ability to control the movement in that range skilfully. Many gym based movements and exercises can be completed through a full range of motion without high skill levels since the speed and complexity of those movements aren’t demanding. However when we look at more complex movements like Olympic lifting, plyometric movements or skill based movements in sport such as throwing, jumping, leaping and gait patterns, we need to consider how the varying speed and acceleration through joint range to provide precision movement needs to be trained for.

By adding a skill element to mobility work, such as control of balance or acceleration we immediately make the movement more difficult, and if we can match the demands of that movement to what we require for a given sport we’ll see improved ability. Routines that challenge mobility, balance and skill are commonly seen in Yoga and Pilates type movements, which is one reason these have become popular with running and cycling coaches in recent years.

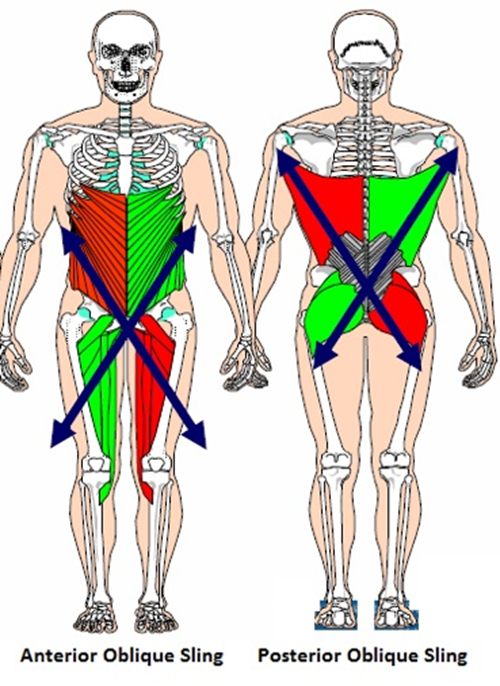

Control of acceleration within movement is another key skill in being able to control force production through a functional range of motion; i.e. throwing or punching or control of impact forces in gait pattern. If we look at gait pattern in running as this is an example that applies to the most sports, one of the key elements in control of run gait is the control of unwanted lateral movement and coordination of the anterior and posterior oblique slings.

Lateral forces during the foot-strike can cause unwanted movement through the hip and knee which decreases efficiency.

It may also increase injury risk through poor joint loading.

The anterior and posterior oblique slings are groups of muscles that work together to produce contra-lateral rotational forces that we use for walking, running and throwing. They form “X” like patterns across the body with each anterior sling working with its partner posterior sling to produce rotation. So how does this link with mobility? Well, the faster we move through a range of motion the more control or skill we require. The body is pretty good and detecting when we’re not in control of a movement, and out of self-preservation will limit range if it feels a movement is not controlled. The issue here however, is that this inhibition of range can produce faulty movement which decreases movement efficiency and can lead to poor movement patterns and faulty joint loading.

If we want to be truly flexible through performance of athletic movements we should include dynamic mobility work that forces balance and control of complex movements through maximal range of motion. Using the anterior and posterior slings as an example a simple movement that can be performed is a reverse and a lateral lunge to apply force through the hips, glutes and shoulders through the end range of the movement.

To target either the anterior or posterior sling depends on how you finish off the movement.

Figure 2 shows a frontal (lateral) and sagittal (back/forward) lunge which loads the anterior oblique sling. The stress lines through the clothing actually mimic the direction of load across the muscles of the hip flexors, obliques and pectorals.

The same lateral and reverse lunge movements can be adapted to load the posterior oblique sling by changing the upper body position and arm movement. Doing this adds more load through the glute max, and opposite side latissimus dorsi.

These movements should be performed dynamically, starting with a comfortable range and speed, then gradually increasing the range with each repetition, and then increasing the speed of the return from the end range. The greater the level of control, the further into the range of motion and more speed you’ll be able to manage before losing form.

These movements can even have forms of resistance added to them to increase the difficult, and then we’re dealing with that area of when does a dynamic stretch become an exercise? When we consider that flexibility is an equal component of fitness just as strength, and we begin to understand it’s importance in true athletic performance, perhaps it’s time to start looking at how we structure workouts and the significance we assign to mobility and skill work. Because if these components of fitness are so important at determining performance, maybe we should stop thinking of them as something we do as part of our warm-up, and looking at how to incorporate and challenge them as part of any training routine as a whole.

Blog originally by Phil Paterson