The game changers movie – why It’s riddled with scientific inaccuracy

Blog banner photo credit: The Game Changers 2019

A couple of months ago a film with the name ‘The Game Changers’ was added to Netflix after a lot of pre-release hype. The film features a number of athletes and medical professionals espousing a plant-based diet and…

OK, so while I was writing the introduction to this piece I became fully aware that it wasn’t really necessary to do an intro because, let’s be honest, you know what The Game Changers is already even if you haven’t watched it. It’s pretty safe to say we’re a little late to the party when it comes to writing this response, but this isn’t because we’ve been kicking our heels. It’s because we wanted to let the dust settle from the immediate, inevitable responses which look to analyse the film itself and then present this – an alternative narrative.

In this blog we’re not about to create a detailed, itemised breakdown of various grievances we have with the film. That’s been done to death by people who were really keen to make sure you knew the ins and outs of the flaws with the production as quickly as possible, and so we’re not about to add something else to the pile as it would be redundant. Many of those blogs are great, don’t get me wrong, I just don’t want to rehash what has already been said by many. Instead I’d like to write a piece on how I, as a person who tries to be unbiased, would have created a documentary about plant-based diets, health, and sports performance. There’s a fair bit of ground to cover, though, so I’ll do this in two parts.

Of course, to justify writing this in the first place I do need to give you a little background on why I think the film fell short, or rather, where the film did not meet their implied goals. I’ll start there before looking at the side of the discussion about which The Game Changers pretends to care the most; sports performance.

You’ll have to come back to a part 2 about the health effects of eating animal products.

So, let’s get in to it.

P.s. if you like to listen or watch instead of reading we dissected our thoughts over on Ben Coomber Radio (a cheeky 60 minute show), jump on over and listen. On the podcast or watch below on YouTube.

Introduction

If you’ve read a load of responses to The Game Changers and you just want to skip ahead to the unbiased assessment of the impact of plant-based eating on sports performance just scroll down to the red text. You’ll save about 5 minutes of reading.

First off, The Game Changers is a film rather than a documentary. The definition of a documentary from Google Dictionary is:

“Using pictures or interviews with people involved in real events to provide a factual report on a particular subject.” [Emphasis mine]

This is kinda-sorta what The Game Changers does because it’s not like they tell out-and-out lies or make data up, but at the same time this is no honest, factual report. To give a factual report on something you would really need to present everything that is relevant – the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. When you don’t do that you have instead created propaganda, the definition of which is:

“Information, especially of a biased or misleading nature, used to promote a political cause or point of view”.

Propaganda isn’t necessarily misinformation, rather it is information presented in a way that is not designed to inform, but to convince. It’s not even necessarily a negative thing (though it sounds like it is), advertising is propaganda, for example. The problem isn’t with propaganda per se, but with propaganda that is presented as being a balanced and fair assessment of the truth.

The difference between a documentary and propaganda looks like this:

- The Tourism Board of Westoros (the place in Game of Thrones) produces a ‘Documentary’ which is specifically designed to show only the good things in order to entice people to go. It illustrates the beautiful countryside, the incredible cities, the vibrant populations and the opportunity to travel to the tropical lands near Dorne for sun, sea, sand, and excellent wine.

- Honest film that also mentions frequent battles/raids, corrupt government officials, dragons, and the whole White Walker thing.

Both examples are truthful but while one is designed to inform you, the other is designed to convince you. Propaganda is often not based in lies of commission (direct statements that are false) but lies of commission: the presenting of an incomplete and thus skewed picture. Basically, it’s a bunch of truth, it’s just not all of it.

Advertising does this all the time, when did you last see an advert for Haribo that spoke about dental health? However, the thing is we expect adverts to do it. Nobody seeing an advert thinks “Yep, that is a fair and balanced analysis of the facts designed to let me make an informed decision”, rather they understand that the person that created the ad is trying to sell them something.

This is not so in The Game Changers which has the implicit goal of informing the viewer of some unbiased findings from rigorous research. The narrator speaks about how he became injured, then spent 1000 hours over 6 months researching nutrition and recovery before coming across a secret (that’s 5.5 hours per day 7 days per week, by the way… doubt…) which he now wants to tell you because you’ve been lied to by ‘big meat companies’. The film uses this to suggest that what follows is a simple presentation of the current body of evidence.

But it isn’t.

The Game Changers was a film created with the express purpose of convincing you to change to a plant based diet – in fact I would argue that it’s designed to convince primarily men to switch to a plant based diet given that all of the test subjects used were men, that they talk about masculinity and meat, and that there’s an erection experiment. This may be because women are twice as likely as men to become vegan or vegetarian already (at least they were when data were collected in 2013 (1)) and so that battle is already won? Who knows, that’s just my opinion.

What’s interesting is that in the film itself, the narrator outlines the way that this same tactic was used to convince people to smoke cigarettes, then to eat more and more meat, they make some excellent points about how manufacturers were able to create distrust in the research linking smoking to cancer, then the way that meat producers have linked meat consumption to manliness (more on this later, it’s an interesting area to read in to). This tells me that the producers know exactly what they’re doing, which leaves the whole thing feeling a little bit slimy, even if they’re well intentioned.

Are they well intentioned? Well, let’s see who the main people behind the project are. Who produced and funded the film?

Note: I’m not the type of person to point to research’s or a project’s funding and be all “AHA! You are funded by X and so everything here can be dismissed!” – people do this far too readily in my opinion. Study funding and the personal ideology of people presenting information should be a red flag, yes, but these are not a good enough reason to dismiss things out of hand, that’s just people being a sloppy sceptic. Funding is just a red flag which should tell you that you need to be extra careful when looking at the actual arguments, facts, and points being put forth on their own merit.

That said when we look at who is behind The Game Changers it’s not hard to see why the outcome of the film was what it was…

- James Cameron Executive Producer and founder and CEO of Verdient Foods, a pea protein company.

- Suzy Amis Cameron Executive Producer and founder of Verdient Foods.

- Jackie Chan Famous person who has recently been speaking out a lot about Animal Rights.

- Arnold Schwarzenegger Also a famous person who has recently become an outspoken Vegan Diet promoter and has long-been an environmentalist (two topics that can’t really be separated), and is said to be bringing out a vegan protein powder.

The other contributors are all also plant based advocates, for example Dr. Dean Ornish is a long-standing plant-based diet promoter. He once had a very interesting back and forth in The New York Times and Scientific American with another highly credentialed professional about diet and heart disease. Basically his opponent, Melinda Wenner Moyer, claimed that his statements about meat and saturated fat were not only out of line with the current research but in many places contradicted it entirely.

Looking at the Wikipedia pages for each doctor that crops up to see where their opinions lie is a fun game to play, with most selling vegan diet products, or being involved with other Netflix productions like Forks Over Knives.

Now to be clear, I’m not saying that the facts these individuals gave are invalid because they have opinions, and I’m not saying that it’s a good idea to pay no attention to plant based advocates when they advocate plant based diets on the grounds that they follow plant based diets. Indeed, that would be entirely stupid – a person who has read that smoking is bad for you will probably avoid smoking and tell you to do the same, and we shouldn’t dismiss them on the grounds that not smoking is their bias. What I’m saying is that an honest documentary – rather than a propaganda piece – would have involved contributors that were willing to present data from both sides of the discussion, because while The Game Changers presented the scientific case as being an open and shut case, the truth is far, far more complicated than that.

The issue at hand is known as ‘cherry picking’. Cherry picking is a pretty simple concept – work out what you want to say, find the studies that could be used to demonstrate what you want to say, then show those to people while not mentioning studies that don’t agree with you. It’s easy to do, and there are a lot of subconscious things that make us do it including confirmation bias and the ostrich effect, but for now I’ll leave that point alone because we’ll get to the research soon enough.

Finally, before we get into the good stuff, I want to quickly outline another key thing that propaganda pieces often do. Something that is mentioned explicitly in the film without a hint of irony – association of a product or idea with celebrities and famous people.

We should all know that personal anecdotes basically don’t mean anything to anyone other than the person with the anecdote. If you do something and your sports performance or health improves, you don’t know whether:

- It was the ‘thing’ you did or the replacement of the ‘thing’ you used to do that made the difference. (i.e. Do you feel better now you eat eggs for breakfast, or now you don’t eat Cinnamon Grahams for breakfast? More broadly, and to offer a spoiler for what is written below, do you feel better because you follow a plant-based diet, or because you stopped eating a bunch of garbage all the time?)

- It was something else that is related but isn’t the ‘thing’ itself. (Have you really become leaner since you cut out carbohydrates, or have you become leaner now that you don’t eat 5 cookies per day as your carbohydrates? Do you have more energy and better recovery now you cut out meat, or is it that you replaced it with a lot of sources of both protein and carbohydrate so that you’re now better fuelled?)

- It was something else completely unrelated (Have you really become a better athlete since you turned vegan, or would you expect to become a better athlete after an additional few years of hard training? Do you have more energy now you’ve started taking that supplement, or have you started paying more attention to your energy in general and that’s caused you to sleep better?)

All really important distinctions to make.

A lot of the time this is a little intuitive – “Just because it works for you, that doesn’t mean it’ll work for me”, but humans are really, really, really bad at statistics and we tend to idolise people too quickly. A combination of these two things just throws off our scepticism entirely.

If your friend told you that they had much better performance at work and that they attributed it to the fact that they started drinking hot chocolate, you’d have some questions. What were they drinking before? Was it because they benefitted from the additional calories? Have they started having a proper bedtime routine so improved sleep quality, and they’re just blaming the drink? What about the other millions of people drinking hot chocolate and staring blankly at spreadsheets?

But if you heard that 20 different successful CEOs all started drinking hot chocolate then made millions, with each telling you their anecdotes, you’d probably start to believe it, especially if one of your friend then started to drink it and tell you they had more energy. These anecdotes are each just as unreliable as each other (the plural of anecdote is not science, btw), and we’re still forgetting the millions of people who don’t have this benefit. But, because these are people who know what they’re doing in business we assume they know what they are doing elsewhere, and 20 people seems like a lot even though at the time of writing that is 0.00000025974026% of the world’s population and thus not really a representative sample.

Propaganda is effective, but we need to see through it. We need to ask the question “OK, that’s what the filmmakers want me to see, but what did they not want me to see? What we’re being shown is interesting, but what are we not being shown?

And rather than simply pointing out that Patrik Baboumian has never competed in the World’s Strongest Man and that his diet is hardly “only plants”, or that it’s not that surprising that Bryant Jennings felt better after moving away from a diet of canned spinach, Popeyes chicken and KFC, I thought I’d go for a quick walk through the data linking plant based diets and both health and sports performance.

If you skipped ahead – here’s where you need to stop scrolling

So here’s what we’re going to do: In this instalment we’re going to look over sports performance on plant based diets – what effect (if any) is seen between plant based and omnivorous athletes and what, if anything, the plant based athletes reading this need to take into consideration when trying to maximise performance. The Game Changers suggests on numerous occasions that Plant Based Diets (from here on in, PBDs) are superior for a number of reasons, and yet many who are a little averse to eating less meat seem to believe that PBD followers are all frail skeletons that eat grass, so it’s time to look to what’s actually true.

Then, in part 2 we will turn our attention to health. While The Game Changers’ headline seems to be about sports performance (and really specifically recovery from sports injuries) it takes a whole bunch of side-lines into this area and so it’s important that the conversation is continued.

I do want to say at this point that I could not POSSIBLY outline the entirety of the research that looks at the influence of plant-based diets on every facet of health because to do so would require writing an entire book on the topic and you didn’t sign up for that (these blogs will be long enough as it is). As such I’m going to focus on the health issues that the film itself focused on:

- The presence of fat in your blood after eating and the influence this has on endothelial function

- Inflammation

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Cancer

I’m expressly not going to discuss the environment, though. I’m not an ecologist and won’t pretend to be one on the internet.

What I am going to do is something the film didn’t do, and that’s define my terms. These are as follows:

- Plant based diet: A diet that is mostly plants by volume

- Vegan diet: A diet that contains no animal products

As you can see there is a difference, and an important one. While all health-conscious vegans are following PBDs, not all plant-based dieters are vegan. In fact, I would argue that most health-conscious omnivores follow plant-based diets because, when you look across a week, they eat more plants than animal foods gram by gram. This matters when we look at research that discusses the two because while The Game Changers pretends that they’re interchangeable terms, or that eating meat and eating plant-based diets are completely mutually exclusive, this is not remotely true.

And as a final bit of preamble, I’m not going to really address some of the sillier things in the film such as comparing humans to gorillas or oxen. The reason that Gorillas get enough protein to be massive while eating almost exclusively plants is that they eat KILOS of food per day. Gorillas-World.com (which are probably a pretty reliable resource for this kind of thing) puts the figure at 18-20kg of plant matter per day (2), then oxen spend most of their day eating and have four stomach compartments which is a little different to our digestive setup…

The Game Changers makes a point of stating that our digestive system is far longer than that of carnivores in an effort to say we aren’t ‘meant’ to eat meat, but they conveniently missed out the fact that our digestive system is also way different to that of herbivores, meaning that we don’t digest or ferment cellulose all that well, and so we don’t absorb plant calories nearly as well. We’re definitely not carnivores (our stomach acid isn’t acidic enough, we can’t make Vitamin C…) but we’re not herbivores, either – we’re omnivores if we’re making a “we should eat how our ancestors ate” argument, and if I was to create a documentary on PBD’s, health, and sports performance, the first scene would probably lay that foundation

Should we eat what our ancestors ate?

Has it ever struck you as strange that we discuss vegan diets in relation to health and performance at all? It should. If you look at the specific food choices of individual athletes you will see that these vary broadly across different cultures, different sports, and of course between different athletes in the same sport. Indeed, it would be strange to find out that everybody on a certain sports team or training in the same gym made the exact same food choices every day, varying only their portion sizes, yet no one really talks about this variance.

If one athlete eats a diet that is primarily based around their Italian roots and another eats a diet primarily based around their Indian roots then they will end up with completely different dietary habits day to day but there’s nobody out there comparing the Indian diet to the Italian diet and trying to find out which is better for Triathlon performance.

It’s only when a person specifically removes animal products that this conversation arises and the question we need to ask is why?

The primary reason is probably that plant-based diets are almost certainly vastly different to the diet of our ancestors (3), with animal product consumption not only being common amongst bonobos and chimps (3) (our closest relatives), but likely being crucial for our own evolution (4, 5).

Now I need to be careful here because it’s easy to be misconstrued when making this claim. Here I’m not saying that we should or have to eat meat because our ancestors did – that would be an appeal to nature fallacy. I’m also not saying that our ancestors ate ONLY meat, as explained by Aiello and Wells (5) here when they outline the evolution of the genus homo to which we belong:

“It is probable that meat comprised a greater proportion of the Homo ergaster diet than it did for the earlier and contemporaneous australopithecines and paranthropines. However, it is unlikely that meat by itself would have met the increased energy requirements of Homo ergaster…Meat protein is easier to digest than plant protein and even with a limited amount of fat would still have been a valuable source of essential amino and fatty acids, fat soluble vitamins, and minerals. It would satisfy nutritional requirements with a lower dietary bulk. This would allow increased reliance on plants of lower overall nutritive quality but high carbohydrate content, such as underground storage organs, to provide the majority of the energy to fuel their larger bodies. Carbohydrates also have a protein sparing advantage over dietary supplementation with fat. In situations of calorie restriction such as might be expected during the dry season on the African savanna, a diet supplemented with carbohydrates is more efficient than one supplemented by fat in sparing limited protein from being metabolized for energy”

Here what I am saying is that meat consumption is something we evolved doing and that we do cross-culturally. Indeed, the evolution to human-ness probably involved a significant increase in meat consumption compared to our ancestors, with chimpanzees consuming roughly 5% of their diet in the form of meat and modern hunter-gatherers being closer to the 20-50% mark (6). Other research has suggested that the evolution of humans from our common ancestors with chimps involved an increase from 10% of the diet being meat to 20% of the diet (6), but regardless of the exact % the truth of the matter is that meat was a key part of our evolutionary past.

The reason this is important is that our meat-consuming history makes meat consumption not a culturally learned norm, but an intrinsic part of normal human behaviour. This may be especially the case for men who demonstrate a far stronger implicit preference for meat and a stronger belief that meat conveys masculinity (7). While it is common to believe this is an artefact of modern advertising this may be far older – consider the following from Love and Sulikowski (7):

“Chimpanzees, like human hunter-gatherers, engage in cooperative hunting and have a resultant social hierarchy, where successful male hunters gain a higher social position and access to meat amongst other males. Larger, more physically robust males typically dominate other males and gain greater status in both human hunter-gatherer tribes and the wider animal kingdom. As meat consumption engenders greater physical condition, which in turn may enable better hunting performance, the successful hunting of meat could create a positive feedback cycle, whereby successful hunters may dominate other males in both physical and social status. Successful hunters and providers of meat in human tribes are routinely afforded a greater respect and position by other males in the group”. In this way, many anthropologists suggest, meat consumption may be one of the fundamental sources of gender roles.

This is all to say that meat consumption is the norm, and it’s not the norm for cultural reasons or because there’s some fat guy in an executive suite somewhere twirling his moustache and laughing at how he’s tricked us into buying his products. As such, unlike the decision between pasta and rice, the decision to consume or avoid meat (and other animal products) represents a shift away from the norm and a shift away from human evolutionary dietary tendencies. This doesn’t make it wrong, but it does mean that we need to consider whether there are consequences to it, just like we’d need to wonder if there were consequences to an individual deciding to avoid other evolved tendencies like interpersonal relationships or staying warm. We don’t HAVE to do as our ancestors did – our ancestors (especially in our evolutionary past) almost certainly routinely practiced cannibalism, rape, and infanticide which I like to think we can all agree are bad – but the idea that animal product consumption, despite being a natural part of our past, is bad for our health or physical performance is a bit of an extraordinary claim…and those require extraordinary evidence.

So, what IS the evidence linking modern sports performance and the consumption or avoidance of animal products?

Mechanisms vs. outcomes

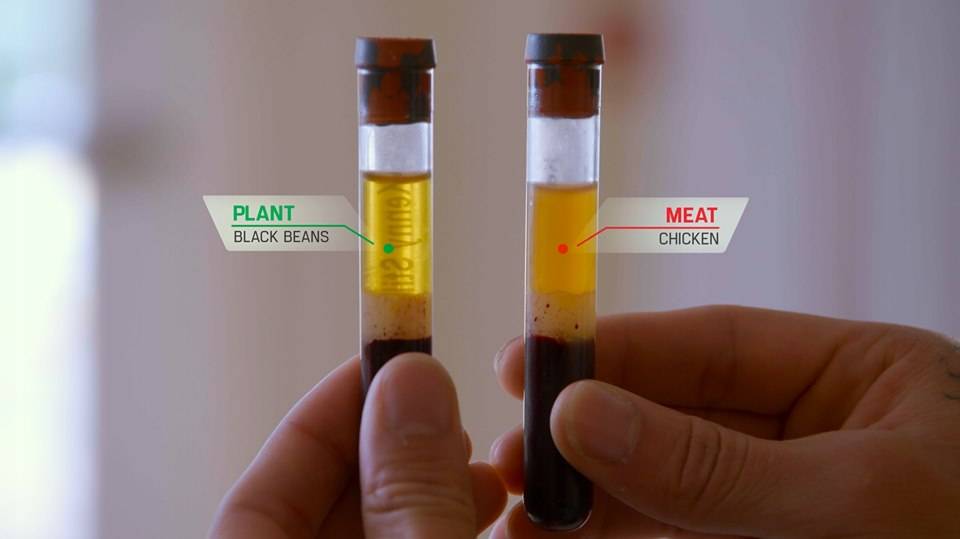

There are a vast number of ways that we could answer the question “how does the avoidance or consumption of animal products affect exercise performance?”. If I wanted to appear really scientific and convince people that avoidance is wise, I would do this by suggesting various mechanisms by which animal foods could potentially harm performance. For example, I could highlight that high fat animal foods cause a reduction in endothelial function in small pilot studies (8) and then demonstrate this by doing a completely unrelated test on three athletes eating either meat or vegan burritos and then showing that after eating dietary fat you get dietary fat in your blood (which is a normal part of nutrient metabolism and not the same thing at all).

Image credit: The Game Changers 2019

But that would be dishonest. Indeed, it would be completely dishonest to do this considering the reference that they used…I mean I used…demonstrates that when consuming a source of monounsaturated fat and antioxidants alongside meat the effect on endothelial function isn’t seen. That’s a weird thing to leave out, isn’t it? We could also look at other studies that show heart-healthy diets with increased protein from lean red meat still improve endothelial function, too (9), but I’m digressing a little here.

The reason I don’t like looking at mechanisms first when we’re talking about sports performance is because that definitely qualifies as missing the forest because you’re looking at trees. Mechanistic data is important because it can explain and provide evidence for the causal nature of a trend – if we see that vegan athletes perform better or worse than non-vegan athletes, or if we see that people who transition to vegan dieting dramatically increase or impair performance, then that would warrant some kind of investigation and blood flow may be a part of that alongside other things. As such, what we SHOULD do is look at what we see in the real world and then use mechanistic data to explain that, rather than looking at mechanisms and then just making assumptions.

So…

Is there a difference between the performance of vegan and non-vegan athletes?

No.

This is perhaps best summarised by Barr et al in their 2004 review paper “Nutritional considerations for vegan athletes” (8).

“Observational studies of vegetarian and non-vegetarian athletes, and elderly long-term vegetarian and non-vegetarian recreational exercisers have not found differences in performance or fitness associated with the amount of animal protein consumed. Short-term interventional studies in which subjects consumed vegetarian or non-vegetarian diets for test periods also detected no difference in performance parameters based on the presence or absence of foods derived from animal tissues. In line with these findings, previous reviews of the scientific literature have concluded that a well-planned and varied vegetarian diet can meet the needs of athletes.”

This is contrary to both the views of those who would suggest a vegetarian or vegan diet is by definition inadequate for sports performance (the YOU MUST EAT MEAT crowd), but also the newer wave of vegan proponents who suggest that avoiding animal products is in fact preferable. There’s a pretty critical phrase in that quote, though, and it’s this bit:

“…previous reviews of the scientific literature have concluded that a well-planned and varied vegetarian diet can meet the needs of athletes.”

Other research corroborates this, for example Nebl et al found no advantage or disadvantage of a vegan diet for recreational runners (9) while Boldt et al found no difference in quality of life between vegan and omnivorous ultramarathon runners (10) while further analysis of the same data found no difference in markers of physical health, either (11). This is probably no surprise to anyone with a passing understanding of endurance sport – carbohydrate is the primary fuel for such activities and healthy vegan diets, which are based in grains, legumes and other carbohydrate containing foods provide this in abundance, but what about strength sports?

A systematic review of Randomised Controlled Trials on the topic by Craddock et al in 2016 found the following (13):

- No difference in repeated sprint testing between participants when half were consuming a vegetarian diet. Participants were not vegetarians historically and were all supplemented with creatine

- A reduction in oxygen consumption at various different %’s of max heart rate on an ergometer when participants followed a vegetarian diet. Prior diet not mentioned

- No difference in maximal oxygen uptake and muscle contraction strength between vegetarian and vegan diets. Participants were non-vegetarians

- No difference in anaerobic capacity of oxygen consumption between habitual vegetarians and non-vegetarians

- No difference in strength or power gains between a vegan and beef heavy diet. Participants were habitual meat eaters

- No difference in strength gains between vegan or vegetarian diets. Participants were habitual meat eaters

- Almost no difference in strength gains between vegan or vegetarian diets – vegans improved more in the leg extension. Participants were habitual meat eaters

The fact of the matter is that plant-based athletes can absolutely perform well, indeed perform optimally and dominate sports just as well as omnivorous athletes, but this requires some careful planning which shouldn’t be surprising. The simple existence of sports nutrition as an area of study suggests that anyone looking to perform well in athletic fields will need to do something different with their nutrition than the average person, and it stands to reason that any way of eating which is restrictive by definition would create a situation where the individual would need to be even more attentive. Vegan dieting falls into this category, especially when it comes to muscle mass gain and preservation. That doesn’t mean it’s impossible, but it IS a barrier that needs to be overcome.

Image credit: The Game Changers 2019

Various studies have found that those following vegan diets have lower muscle mass than omnivorous individuals. For example, Aubertin-Leheudre and Adlercreutz found that in healthy women of matched protein intake, vegan dieters had less muscle mass (12). The matched-ness of the protein intake is questionable as the researchers used self-reported intake data, but this paper still illustrates the difference in muscle mass between the groups. Vanacor et al reported similar findings when looking at Italian men who were vegan, vegetarian or omnivorous (13). In their study the vegan group had reduced muscle mass (and also were not protected from oxidative stress, for what that’s worth). Now these studies do not provide evidence that vegans will inherently lose muscle mass or that they can’t gain it, but they do provide evidence that in free living conditions, reduced muscle mass is a result of cutting out all animal products and as such additional attention to nutritional strategies for supporting muscle mass is justified. While this would appear to go against the studies listed about performance it’s important to note that there are some differences here:

- The studies cited by Craddock et al were all short-term randomised controlled trials and so not as demonstrative of the effect of long-term vegan eating as they would ideally be

- We need to acknowledge that what happens when non-athletic people are in free living conditions, and what happens when athletes are paying attention to their nutrient intake, probably won’t be the same

In short, vegan diets can work for athletics, and they do not appear to be any better or worse, but attention needs to be paid because at baseline the vegan diet is likely to lacking in some key things necessary for muscle growth and support.

If we take an unscientific look at top athletes today we can point to the fact that the world rankings aren’t dominated by those on a vegan diet as evidence that meat avoidance holds athletes back, but we can also point to a growing minority of vegan superstars as evidence that the alternative works, too.

The question, therefore, should not be ‘can vegan diets support performance?’ because it obviously can. A much better way to frame it would be this:

Your body does not really know or care what you eat. Your specific food choices don’t really make a difference for sporting performance – what matters is consuming the required nutrients, perhaps at the right times. Whether those nutrients are carried by plant-based foods or animal-based foods is by the by. What omnivores need to do in order to get those nutrients is pretty well known by this point, but the questions still remains – What does a person following a vegan diet need to do in order to maximise their performance? And due to the restrictive nature of their lifestyle choice do they need to pay extra attention in a few areas?

Let’s answer those questions now.

How to maximise vegan performance, an overview

The first thing we need to do when discussing any considerations we need to make for vegan dieters looking to maximise sports performance is look at the similarities and differences between the diets. It has been claimed both in the literature (14) and in recent PBD films that vegan diets offer an advantage over omnivorous diets because of a greater emphasis on carbohydrates, micronutrients and antioxidants. These claims are spurious at best for two reasons:

- Scientific evidence for this does not exist (14)

- This makes a blatant fallacy of excluding the middle. We’re not comparing diets of only plants to diets of only animal products, we’re comparing health seeking vegan and health seeking omnivorous diets both of which will be rich in fruits and vegetables (the primary sources of antioxidants and phytonutrients) and of course carbohydrates.

- High carbohydrate diets have been the standard recommendation for years in athletic populations with the International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN) position stand recommending between 3-10grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of bodyweight to athletes of varying training styles (15). There is simply no reason to assume that a plant-based diet would be higher in carbohydrates, unless we are simultaneously making the argument that either a plant based diet is insufficient in protein or fat, a plant based diet is higher in calories, or a non-vegan diet is by definition too high in protein – all of these are arguments based around user error rather than implicit features of the diets in question and so are, to be frank, a bit silly

Basically, unless you forget that non-vegans also eat vegetables and carbohydrate sources, this idea holds no water. In fact, rather than vegan diets offering an inherent advantage they may offer a disadvantage because, as mentioned already, greater care is needed to ensure the individual gets all they need.

Poorly constructed vegan diets predispose individuals to macronutrient and micronutrient (vitamin B12 and vitamin D; iron, zinc, calcium, iodine) deficiencies while also being a potential risk factor for undereating calories in general due primarily to the low energy density of most plant-based foods (14). This is typically advantageous for the general public and almost certainly explains why the relative amount of restriction that a vegetarian has on their diet is predictive of BMI (15) (Vegans are leanest, then BMI increases as you add in more animal foods until you reach omnivores), but it’s a problem in athletes considering that relative energy deficiency is common in this group (14).

Because of this any vegan athlete (as with any other athlete) must ensure that they are at least somewhat aware of their calorie needs and intake (if they aren’t just tracking this directly) and that they adjust their food consumption according to their individual needs at each point in the training calendar.

I would even go so far as to say that most people who try a vegan diet and feel a lack in energy, performance or recovery are struggling with this specific point – you have to make the effort to eat enough calories!

The protein question

It’s at this point that any PBD-following readers roll their eyes, but this is a topic that needs to be discussed because it’s one where there is an insane amount of misinformation coming from both sides. Meat-eaters will often claim that vegan diets are protein deficient by default, while vegan diet promoters will often say that vegans consume more protein than they need.

As always, everyone is wrong but me (I’m mostly joking).

The idea that vegans consume more protein than they need comes from the fact that in general, vegans consume more than the RNI (or RDA if you’re American) which is 0.75g/kilo of bodyweight (0.8 in the USA). Large surveys seem to indicate that vegans exceed this, consuming just over 1g/kg of protein (16), but they consistently are found to consume less protein than their omnivorous counterparts (16, 17) and this could be a problem considering that recent research suggests that the typical recommended intake is insufficient for both general populations and athletes.

The current recommendations are based upon nitrogen balance studies. Protein is the only macronutrient that contains nitrogen, and when amino acids are broken up to be used for energy or the production of carbohydrate their nitrogen is excreted, while amino acids used for some kind of protein synthesis retain their nitrogen within the body. If you measure the amount of nitrogen a person eats and the amount they excrete you get nitrogen balance which is a decent proxy for protein balance. If you consume more than you excrete then you have possibly built muscle, the opposite is true, and if the amounts are identical you have probably maintained muscle – it’s a bit more complex than that because muscle isn’t the only storage site for protein, but that’s the general gist.

The recommendations of 0.75g/kg or so are the minimum amount believed to provide nitrogen balance for the general population (14) – it’s the amount needed to avoid deficiency. Avoiding deficiency is not the same as achieving optimal health, however, and more up to date measuring techniques have revealed that the ideal protein intake for the general population may be 50% higher, 1.2g/kg (14). Many vegan dieters will consume this habitually, or with a small amount of effort, and so it’s definitely the case that the average person who eschews meat isn’t throwing protein sufficiency out of the window.

This is before we discuss athletes, however, for whom recommendations are often far higher.

The current ISSN recommendation is 1.4-2g of protein per kilogram of bodyweight depending on your sport (higher end for strength athletes, lower for endurance athletes) (18), although a recent meta-analysis of all the relevant literature suggests that the figure for those seeking hypertrophy may be 1.6-2.2g/kg (19) and values as high as 3.1g/kg of lean body mass have been suggested while dieting (20). Importantly, this is ‘high quality’ protein, meaning highly digestible protein that contains all of the essential amino acids relevant to human nutrition in appropriate amounts.

Almost all foods contain all of the 9 essential amino acids, from steak to lettuce, but the amount of each varies significantly and this has important implications for muscle protein synthesis, the process through which the human body utilises amino acids for building muscle. Amino acids lacking in plant-based protein sources tend to be most commonly lysine, methionine and in many cases leucine, the key trigger for muscle protein synthesis (14). Vegan diets can provide all of these in adequate amounts provided the individual consumes a wide range of protein sources across the day, with high leucine soy and lentils, high lysine beans and high methionine grains all complementing each other effectively even if not consumed in the same sitting*.

*No. You probably don’t need to combine proteins within a meal.

This is not the only issue with plant-based proteins, however. When judging protein quality for human needs we need to look at it based upon the amino acids contained within the protein, how well these match up with the needs of humans, how well those amino acids can be absorbed through the intestine (which may be limited by various factors including anti-nutrients in the food itself or simply the food matrix – i.e. the fibre content etc) and then how much is used for nitrogen storage as opposed to other kinds of metabolism. This can all be measured using the digestible indispensable amino acid score or DIAAS, and animal-based proteins consistently perform better than plant-based proteins (21).

While it is unclear what implication this has for people who aren’t consuming single sources of protein in a given meal, this has led to recommendations for vegans to consume MORE Protein than their omnivorous counterparts by up to 25% (14), meaning an intake of 2-2.6g/kg may be necessary. As per other athletes, this would ideally be distributed across 4-5 meals per day, in roughly equal portions (18).

A brief commentary on fats

Generally speaking, vegans have a lower intake of fat than do other dieters, with this commonly resulting in a lower serum Omega 3 concentration (14). This is a potential problem because Omega 3 fatty acids can potentially play a role in (21):

- Preventing the generation of excessive post exercise oxidative stress

- Augmenting muscle protein synthesis

- Improving cardiovascular health and function

- Improving immunity

- Increasing muscle mass quality

- Reducing joint pain

Vegan diets do provide Omega-3 but they do so in the form ALA, which must be converted to EPA and DHA, the forms useful for humans. This process can be done but it is incredibly inefficient (ALA converts to EPA and DHA at around 8 and 0.5% respectively (14)) meaning that ALA intake from nuts, seeds, and similar foods would need to be extremely high to achieve the 1-2g intake of Omega 3 suggested for athletes, especially considering that 1/3 of that should be DHA (14). As such, supplementation of algae-based EPA and DHA oils are strongly suggested for those avoiding animal products (and supplementation in general is recommended for those not regularly eating fish).

Micronutrients

The American Dietetics association recommend that care is taken to consume adequate amounts of vitamin B12, iron, calcium, iodine and vitamin D if following a vegan diet. Vitamin D is difficult to get in meaningful amounts through the diet whether vegan or not (22) with primary sources being fish or sunlight, and so I tend to recommend supplementation across the board and won’t discuss it further here. The other nutrients do warrant talking about, though.

Vitamin B12 is important for a healthy nervous system and functional red blood cells, with a deficiency potentially causing megaloblasic anaemia, or a degenerative brain disorder called subacute combined degeneration. Clearly a deficiency in this will not be productive for sports performance. It’s synthesised by microbes in the gut of ruminants like cows and sheep, and so animal products are the primary sources for humans (14). It’s often said that humans historically could acquire vitamin B12 from natural water or dirt on food, but this assumes that these sources were contaminated with animal matter and, in the case of vegetables, not washed which is unlikely. This is not to say that B12 does not exist at all in plant-based foods, however, with fermented foods like unpasteurised sauerkraut, nutritional yeast and marmite containing meaningful amounts, as well as fortified cereals other foods.

Data from the EPIC-Oxford cohort study (23) found that 50% of UK vegans are B12 deficient with a further 21% having low serum levels, with no difference between those who were and were not supplementing. Other studies have found that B12 supplement absorption rates are low, with a 500mcg supplement only resulting in the absorption of 10mcg (14) which could explain this. Intake up to 6mcg per day have been recommended for vegans (14) though the RNI is 2.4mcg. It’s also commonly recommended to have serum levels checked by a doctor as injections may be necessary.

Research indicates that, thanks to a frequent intake of beans and legumes, vegans have a similar Iron intake level as non-vegans (14), but that’s not where the story ends. While male vegans have similar deficiency rates as non-vegans, female vegans are more at risk of being iron deficient (14), an issue that may present either because of the lower bioavailability of the non-heme iron form found in plant foods or because of the higher intake of the anti-nutrients tannin, polyphenols and phytates which can reduce iron absorption (14). As such iron intake needs to be prioritised in this population, with iron deficiency anaemia causing fatigue, tiredness and weakness if left unchecked (14). Interestingly iron deficiency in the absence of anaemia still seems to negatively affect endurance exercise performance, reduce exercise-induced adaptations and increase energy expenditure, too, so an absence of anaemia is not necessarily the absence of a problem (14).

Some have suggested that humans can adapt to different iron intakes with lower levels promoting improved absorption, and so vegans/vegetarians should not worry so long as they meet the RNI (14), though the institute of medicine disagrees and recommends an 80% increased intake for those following a vegan diet (14). For now, recommendations are to consume a wide range of iron containing foods, look to reduce anti-nutrients (especially tannin in tea which may be an issue when consumed alongside iron containing foods) and to regularly check with a doctor as supplementation may be needed.

When it comes to calcium, vegan dieters tend to consume lower amounts, and are sometimes (though not always) found to be at greater risk of fractures as a result (14). It has been suggested that vegan diets are protective of calcium status and bone mineral density due to a higher animal protein intake’s calcium leeching effect on bone minerals, but this is not an evidence based statement (14) – indeed a higher protein intake tends to work synergistically with calcium to augment its ability to strengthen bones (14).

Calcium needs may be increased in athletes due to significant losses in sweat, but as this has yet to be shown in research the recommendation for athletes remains at 1000mg per day which is reasonably easy to get on a vegan diet so long as care is taken. Some plant foods such as spinach or rocket (arugula) are high in oxalates, however, which impair absorption and so are not considered a good source of calcium.

Vegan dieters can also utilise a wide range of fortified foods and milks to assist intake, but must be aware that the calcium content of plant milks tends to be far lower than that of dairy milk and so simply drinking plant milks during the day is not likely to meet needs.

The final micronutrient of relevance is iodine which is often either excessive or lacking in vegan diets depending on the specific choices of the individual (14), with both intake levels being harmful to thyroid health. This stark variation is because almost all dietary sources of iodine are animal products other than one group: sea vegetables which can be excessively high in iodine if consumed very regularly and so are not considered a reliable source by the British Dietetics Association (14). Instead cranberries, potatoes and fortified foods (including iodised salt which is not used as standard in the UK but can be bought) are recommended, with supplementation being an effective last resort.

Assuming a vegan dieter is able to meet all of the above nutrient needs their body will run more or less identically to that of a meat-eater [if you suspect micronutrient issues check out Awesome Daily Dose, a vegan all-in-one high dose multivitamin] They will make dramatically different food choices but as said already so will two different meat eaters, or two different PBDieters, and so that’s not really anything out of the ordinary. If a PBDieter meets the intakes recommended for athletes, they will be as successful as they can be.

There’s one more angle to look at before we close, however.

Muscles and creatine and carnosine

Two substances that play important roles in sports performance are creatine phosphate and carnosine. The former is an energy substrate which can be used to fuel explosive movements like jumps, short sprints and low repetition weightlifting while the latter helps to buffer the lactic acid build up (not TECHNICALLY the right term but we’ll just use it for ease) during intense activity lasting around 1-4 minutes.

Creatine can be consumed through animal products and so, as you would expect, creatine stores in vegetarians are generally lower (14). Supplementation with creatine is very useful for sports performance from a wide range of different angles (24) that don’t really need to be explored here, other than to say that thanks to these habitually reduced stores vegans and vegetarians may benefit more from creatine supplementation than would meat eaters. Interestingly in at least one study creatine supplementation improved memory in vegetarians but not meat eaters (25) which makes sense as 5% of body creatine is stored in the brain. One study with a small simple size, but an interesting finding, nonetheless.

Carnosine, on the other hand, is not directly consumed but is instead synthesised using beta alanine and l-histidine. You have loads of l-histidine, however, so it’s just the beta alanine that you need to boost carnosine and, as you may have guessed at this point, you only really get it from animal products and so vegetarians tend to have lower levels (14). Very little research exists in this area but it’s a reasonable assertion that beta alanine supplementation may preferentially benefit vegans, too.

[Both of which you can get in this one supplement called Performance Blend, should you be interested. Yes, its vegan friendly].

Part 1 conclusion

So, that was quite a read… where are we now?

Simply put, vegan and non-vegan athletes who are both on well-planned diets should not experience any difference in performance metrics, be they strength, endurance, power, hypertrophy, or a combination of the above. If a meat eater eats a low carbohydrate, excessive protein diet they will struggle and so will a vegan who eats an excessively low protein intake, but neither of these examples are ‘doing it right’ so that doesn’t really matter. The point is that your animal product consumption, or lack thereof, is far less relevant than you would think thanks to the ability of modern people to meet their needs either way using the 21st century food options we have.

Eating meat or being vegan won’t improve your performance by default – you need to pay attention – the only reason we need to have this discussion at all is that vegan diets are restrictive by definition. Eliminating many of the most potent sources of key nutrients for sports performance including iron, calcium, protein, and the humble calorie is a risk and so a keen eye must be kept on an individual’s intake of these things, vegan, plant based or not.

Yes, the same goes for omnivores, but those who eat animal products are at a greater chance of getting things pretty much right by accident, hence an increased awareness in vegan dieters. Omnivores DO need to pay attention, however, because there are an absolute ton of health benefits associated with plant-based diets and vegan dieters tend to have better health outcomes.

Meat eaters tend to have better sporting outcomes, too, but I like to think I’ve just demonstrated that the reason for that is incidental rather than causal and so it’s not fair to say that there will definitely be a difference in performance if you don’t consume animal products.

I wonder if the same applies to health?

Join me in part 2 to find out.

Until then please be careful when choosing sources of information. Bias and propaganda are words thrown around a lot but they have a really distinct meaning and should not be ignored just because you see them all the time – if a person wants you to think something (and they have James Cameron money) then can do a really good job of convincing you of that thing by presenting one side of the argument and ignoring (or misrepresenting) the other side. Netflix documentaries aren’t a good source of information for this thing because Netflix doesn’t have a duty of care to fact check what they put out – their only concern is the bottom line; will this make us money?

And this is a shame – The Game Changers had a golden opportunity to tell the world that vegan diets can be really effective for sports performance provided adequate care is taken, but they threw it away by making unnecessary unfounded claims and so making the whole thing look bad. Yes, a few people have changed to a vegan diet but I’d bet my shoes that the majority will be eating meat again within the year, unless they were already thinking about making the transition.

Had they been more honest, and instead discussed a moderate reduction in meat without all of the scare tactics, maybe they could have had a longer lasting impact? If I was an evidence based vegan diet promoter I’d be pretty pissed, to be honest.

But that’s just me…

Written by Tom Bainbridge (Head of Education at The BTN Academy) and edited by Ben Coomber (BTN Academy Owner).

Want to do a free 5 day nutrition course that isn’t biased but evidence-based? Scroll down to the orange box…

References

- Uk.kantar.com. (2019). Kantar – Only 3% of UK self-define as ‘vegan’. [online] Available at: https://uk.kantar.com/consumer/shoppers/2019/only-3-of-uk-self-define-as-vegan/ [Accessed 17 Nov. 2019].

- Gorilla Facts and Information. (2019). Gorilla Feeding – Gorilla Facts and Information. [online] Available at: https://www.gorillas-world.com/gorilla-feeding/ [Accessed 17 Nov. 2019].

- Surbeck, M. and Hohmann, G. (2008). Primate hunting by bonobos at LuiKotale, Salonga National Park. Current Biology, 18(19), pp.R906-R907.

- Psouni, E., Janke, A. and Garwicz, M. (2012). Impact of Carnivory on Human Development and Evolution Revealed by a New Unifying Model of Weaning in Mammals. PLoS ONE, 7(4), p.e32452.

- Aiello, L. and Wells, J. (2002). Energetics and the Evolution of the GenusHOMO. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31(1), pp.323-338.

- Psouni, E., Janke, A. and Garwicz, M. (2012). Impact of Carnivory on Human Development and Evolution Revealed by a New Unifying Model of Weaning in Mammals. PLoS ONE, 7(4), p.e32452.

- Love, H. and Sulikowski, D. (2018). Of Meat and Men: Sex Differences in Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Meat. Frontiers in Psychology, 9.

- Barr, S. and Rideout, C. (2004). Nutritional considerations for vegetarian athletes. Nutrition, 20(7-8), pp.696-703.

- Nebl, J., Haufe, S., Eigendorf, J., Wasserfurth, P., Tegtbur, U. and Hahn, A. (2019). Exercise capacity of vegan, lacto-ovo-vegetarian and omnivorous recreational runners. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 16(1).

- Boldt, P., Knechtle, B., Nikolaidis, P., Lechleitner, C., Wirnitzer, G., Leitzmann, C., Rosemann, T. and Wirnitzer, K. (2018). Quality of life of female and male vegetarian and vegan endurance runners compared to omnivores – results from the NURMI study (step 2). Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 15(1).

- Wirnitzer, K., Boldt, P., Lechleitner, C., Wirnitzer, G., Leitzmann, C., Rosemann, T. and Knechtle, B. (2018). Health Status of Female and Male Vegetarian and Vegan Endurance Runners Compared to OmnivoresâResults from the NURMI Study (Step 2). Nutrients, 11(1), p.29.

- Aubertin-Leheudre, M. and Adlercreutz, H. (2009). Relationship between animal protein intake and muscle mass index in healthy women. British Journal of Nutrition, 102(12), pp.1803-1810.

- Craddock, J., Probst, Y. and Peoples, G. (2016). Vegetarian and Omnivorous NutritionâComparing Physical Performance. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 26(3), pp.212-220.

- Rogerson, D. (2017). Vegan diets: practical advice for athletes and exercisers. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1).

- Kerksick, C., Wilborn, C., Roberts, M., Smith-Ryan, A., Kleiner, S., Jäger, R., Collins, R., Cooke, M., Davis, J., Galvan, E., Greenwood, M., Lowery, L., Wildman, R., Antonio, J. and Kreider, R. (2018). ISSN exercise & sports nutrition review update: research & recommendations. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 15(1).

- Clarys, P., Deliens, T., Huybrechts, I., Deriemaeker, P., Vanaelst, B., De Keyzer, W., Hebbelinck, M. and Mullie, P. (2014). Comparison of Nutritional Quality of the Vegan, Vegetarian, Semi-Vegetarian, Pesco-Vegetarian and Omnivorous Diet. Nutrients, 6(3), pp.1318-1332.

- Venderley, A. and Campbell, W. (2006). Vegetarian Diets. Sports Medicine, 36(4), pp.293-305.

- Jäger, R., Kerksick, C., Campbell, B., Cribb, P., Wells, S., Skwiat, T., Purpura, M., Ziegenfuss, T., Ferrando, A., Arent, S., Smith-Ryan, A., Stout, J., Arciero, P., Ormsbee, M., Taylor, L., Wilborn, C., Kalman, D., Kreider, R., Willoughby, D., Hoffman, J., Krzykowski, J. and Antonio, J. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1).

- Morton, R., Murphy, K., McKellar, S., Schoenfeld, B., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A., Devries, M., Banfield, L., Krieger, J. and Phillips, S. (2017). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine, pp.bjsports-2017-097608.

- Helms, E., Aragon, A. and Fitschen, P. (2014). Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 11(1).

- Gammone, M., Riccioni, G., Parrinello, G. and D’Orazio, N. (2018). Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Benefits and Endpoints in Sport. Nutrients, 11(1), p.46.

- Ods.od.nih.gov. (2019). Office of Dietary Supplements – Vitamin D. [online] Available at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Vitamin%20D-HealthProfessional/ [Accessed 17 Nov. 2019].

- Gilsing, A., Crowe, F., Lloyd-Wright, Z., Sanders, T., Appleby, P., Allen, N. and Key, T. (2010). Serum concentrations of vitamin B12 and folate in British male omnivores, vegetarians and vegans: results from a cross-sectional analysis of the EPIC-Oxford cohort study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 64(9), pp.933-939.

- Frank, K., Patel, K., Lopez, G. and Willis, B. (2019). Creatine Research Analysis. [online] Examine.com. Available at: https://examine.com/supplements/creatine/ [Accessed 21 Nov. 2019].

- Benton, D. and Donohoe, R. (2010). The influence of creatine supplementation on the cognitive functioning of vegetarians and omnivores. British Journal of Nutrition, 105(7), pp.1100-1105.