Plant based protein powders – Ideal option or poor imitation?

Can you build muscle on a vegan diet?

When it comes to health and performance, protein is kind of a big deal.

Now that of course isn’t to say that the other macronutrients are unimportant (just to pre-empt any misunderstandings), but it is to say that whether you’re hoping to grace the stage as Mr. Olympia, put up a world beating full power total, join the ranks of 4-minute milers, or simply get older with the smallest possible amount of age-related decline, it would benefit you to gain some kind of understanding about your protein needs.

Go back a few years to the days of ‘athletes just need pasta’ and the above paragraph may have been controversial, but I don’t think that is the case anymore. Indeed, ask anyone with just a passing understanding of nutrition for performance and/or health and they’ll tell you that protein is one of the things you need to get right…But what does that mean? Today I’ll be exploring that question with a mind for one specific angle of analysis: What role, if any, do plant-based protein powders have? After all, while it is still the case that animal-based proteins make up the bulk of protein consumed in Western countries, there is a growing amount of concern from consumers about both environmental and ethical effects of animal-based foods, and those people still need to make gains, right?

To be clear there are three primary functions for dietary protein within the context of this article:

- Maximise muscle protein synthesis

- Halt muscle protein breakdown

- Provide substrate that can be used to build new or repair old muscle

All of these functions lead to reduced muscle loss at rest, or increases in muscle mass after resistance training in either young or older adults (1). This comes along with increased strength, athleticism, cardiovascular health, blood glucose management, bone health and more, and so it stands to reason that anybody interested in human wellbeing would want to ensure that they and their clients met their protein needs. Fortunately, it’s not too difficult to make protein recommendations to do that.

How much protein do you need each day?

1 – Adequate protein must be consumed during the day. While recommendations vary, intakes between 1.6-2.2g of protein per kilogram of bodyweight seem to be a rough ceiling for increased muscle mass over time when in a calorie surplus (2). When in a calorie deficit the most commonly recommended figures are 2.3-3.1g/kg of lean body mass or 1.8-2.7g/kg total body mass (3). These figures should be approached with some degree of caution, however, as any recommendation based on total body mass is vulnerable to the influence of higher body fat, with that tissue not meaningfully influencing actual need.

To be more explicit, an individual with a lean body mass of 80kg will require the exact same amount of protein whether they actually weigh 90kg or 130kg, and so I ask that (should you use these numbers in practice) you opt for the lower end of the hypertrophy recommendations for those you would subjectively refer to as ‘having a little bit to lose’, and you use lean body mass fat loss recommendations where possible. This may seem somewhat vague and open to interpretation, but that’s the beauty of nutrition as an applied science.

2 – That protein needs to be distributed evenly throughout the day. It’s now generally accepted that a muscle full effect is seen when measuring the muscle protein synthetic response to feeding, meaning that muscle protein synthesis (MPS) is elevated for a finite amount of time irrespective of there being sufficient amino acids in the blood. In practice consumption of protein seems to maximise MPS within around 90 minutes of eating, with a return to baseline being seen around 90 minutes later (5). Interestingly but of little relevance to this specific piece, the duration of MPS activation seems to be longer after resistance training, which may in part explain why lifting helps increase muscle mass (5).

3 – The protein needs to be of high quality, and it is to this point that we need to turn our attention if we’re interested in plant-based protein powders – here’s why…

The vast majority of protein research has historically focused on animal-based proteins (6). Indeed, the points made above related to MPS and the muscle full effect come from trials that used animal-based proteins and this is for one simple reason: animal-based proteins tend to be more effective at promoting MPS due to their higher quality, but what does that mean?

What is protein quality?

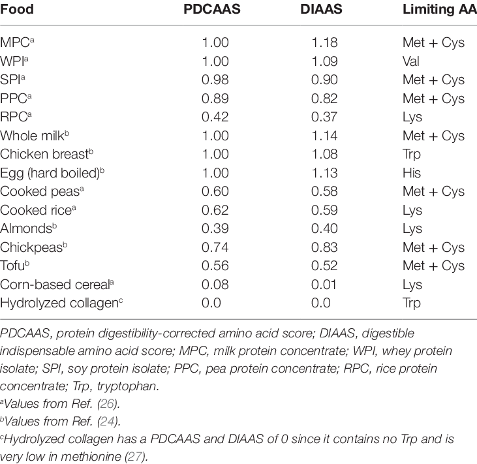

Measures of protein quality seek to apply a numeric rating to various protein sources, with the two most commonly used being the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) and the more recent Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). Both serve largely the same function – they rate proteins by how useful they are for human nutrition given various factors that influence that kind of thing, with the main differences being that the DIAAS accounts for ileal absorption of amino acids whereas the PDCAAS doesn’t, and with the DIAAS comparing proteins to a theoretically perfect one and the PDCAAS comparing proteins to egg protein. The rest of the score tends to be made up of a comparison between human requirements of each amino acid*, the amino acid content of the food, and anything that might reduce absorption, like food-derived anti-nutrients.

*Proteins in food and your body are made up of amino acids. There are 20 relevant to humans, of which 9 are essential meaning your body can’t make them and so you need to get them from food.

Whichever you look at, plant proteins don’t do as well as animal-based proteins, especially when you compare plant proteins to animal-based protein powders like whey (table below taken from (6))

This of course has one interesting exception as you can see in the table above, soya protein isolate, and this is reflected in a 2018 meta-analysis of long-term studies (6 months or longer) which found no difference in lean body mass accrual when comparing soy to other proteins including whey (7).

Does this mean you can’t build muscle with plant protein?

Things may be a little more complicated than that, however. First, the studies in the above meta-analysis were generally in small numbers of people, and the majority involved untrained people – for reasons beyond the scope of this piece untrained people gain muscle more or less no matter what you do, so their outcomes are hard to extrapolate. There were further reasons why we can’t take the above analysis as the final note on this problem, too, including variations in study design, low protein intakes across the board (all below the 1.6 lower end I recommend above), and a few others all listed by the authors themselves but today I want to focus on one key thing that they discuss:

In acute studies (Usually 3 hours or less), soy protein increases muscle protein synthesis less than whey (7). Indeed, even when essential amino acids are matched soy is often outperformed by it’s milk-derived counterpart (8). Perhaps more alarmingly, while 40g of soy isolate was able to increase MPS in elderly men after exercise, 20g was not, and neither dose was able to increase MPS at rest (9) – whey, however, was effective at 20g even at rest (9).

This is almost certainly down to the lower leucine content of soy, and indeed most plant-based proteins when compared to animal proteins (especially whey). Thanks to activation of the mTOR pathway, leucine is able to effectively stimulate muscle protein synthesis, and multiple studies have found that the MPS response to plant-based protein is equal to that of whey or other animal based proteins only when leucine is matched (10). This indicates that plant-based proteins can work for muscle building and maintenance just fine – you just need to consume a higher dose, or a regular dose with leucine added.

For example, in a study in older men (11), 35g of wheat protein did not increase MPS as much as 35g of whey did, but 60g of wheat protein which matched the leucine content of the whey did (indeed it did so to a greater extent but there are more calories in that much protein so that’s to be expected).

And to this end, a growing number of sports nutrition companies have started to experiment with powders comprised of mixed sources with the aim of combining amino acid contents to create something that closely mimics whey. This would, in theory, give plant-based athletes an option far superior to soy protein, while still adhering to their plant based principles.

What is the evidence surrounding mixed-source plant protein powders?

Take a look back at the table above. You will notice in the final column that a “limiting amino acid” is listed. This term is somewhat self-explanatory. Within each food that you eat the ratio of each amino acid will differ, meaning that 5g of protein from steak and 5g from some asparagus will be made up of the same stuff, but the actual composition will differ radically and that has a meaningful effect on the MPS response. There is an ‘ideal’ ratio in which the essential amino acids can be found, and this is best provided by dairy proteins, but even this is limited by a slight reduction in one amino acid or other. In many of the proteins listed, as you can see by both the PDCAAS and DIAAS this doesn’t make a practical difference, but further down the table those limiting amino acids start to really matter. Fortunately, however, while one protein source may be lower in one amino acid this can be ‘made up’ by a different source, and this theory has given birth to a booming plant-based protein powder market that uses proteins with a complete amino acid profile.

This theory is bolstered by studies that have found that consumption of a protein blend comprised of a 1:1:2 ratio of soy, whey, and casein protein results in equal MPS stimulation when compared to whey in both young (12) and older (13) people. While this only involves a 25% plant protein inclusion, it does provide evidence for the fact that the MPS response to a protein source containing plant-derived amino acids can do the same job as one from animal sources so long as the amino acids are complemented well.

Unfortunately, however, this is far from proof that combined proteins that are 100% plant derived will have the same effect…and this is all we have.

While it makes perfect sense that combining plant based proteins to create an amino acid profile equal to that of whey would enable a plant based protein powder to provide the same MPS response, as of September 1st 2020, no experimental evidence exists to support this claim(10). This is an emerging area of research, however, and I would expect that in the 18-24 months following publication of this article we will see a large number of studies reaching publication to elucidate exactly what happens when you combine complementary sources like pea and rice.

Final Thoughts

Indeed, to complete this article I need to circle back to the three points I raised at the start. Protein is ideally consumed in an adequate amount, at regular intervals, and in high quality. This consumption, if muscle mass is the goal, then needs to be combined with proper sleep, well-programmed training, and a sufficient calorie intake and given this whole-lifestyle view the specific protein powder you choose is actually a relatively small part of the whole equation.

Given the meta-analysis noted above on soy (for all the flaws it has) which notes no difference over time when comparing soy to whey – at least in untrained people – and a well-reported pilot study from 2019 which found no difference over 8 weeks when comparing pea protein alone to whey (14), I’m going to finish on the following prediction:

Even if future research finds that the MPS response to combined plant-based protein powders is lesser than the response to whey (I don’t expect it will be), it will be by a very small amount, and when taken within the context of the whole lifestyle the actual difference to strength, muscle mass, and health over the course of months and years made by whey vs plant blends will be so negligible that, honestly…it just won’t matter which you use.

References

1 – Witard, O. C., Wardle, S. L., Macnaughton, L. S., Hodgson, A. B., & Tipton, K. D. (2016). Protein Considerations for Optimising Skeletal Muscle Mass in Healthy Young and Older Adults. Nutrients, 8(4), 181.

2 – Morton, R.W., Murphy, K.T., McKellar, S.R., Schoenfeld, B.J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., Aragon, A.A., Devries, M.C., Banfield, L., Krieger, J.W. and Phillips, S.M., 2018. A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British journal of sports medicine, 52(6), pp.376-384.

3 – Helms, E.R., Zinn, C., Rowlands, D.S. and Brown, S.R., 2014. A systematic review of dietary protein during caloric restriction in resistance trained lean athletes: a case for higher intakes. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 24(2), pp.127-138.

4 – Phillips, S.M. and Van Loon, L.J., 2011. Dietary protein for athletes: from requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of sports sciences, 29(sup1), pp.S29-S38.

5 – Atherton, P.J. and Smith, K., 2012. Muscle protein synthesis in response to nutrition and exercise. The Journal of physiology, 590(5), pp.1049-1057.

6 – Phillips, S.M., 2017. Current concepts and unresolved questions in dietary protein requirements and supplements in adults. Frontiers in Nutrition, 4, p.13.

7 – Messina, M., Lynch, H., Dickinson, J.M. and Reed, K.E., 2018. No difference between the effects of supplementing with soy protein versus animal protein on gains in muscle mass and strength in response to resistance exercise. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 28(6), pp.674-685.

8 – Tang, J.E., Moore, D.R., Kujbida, G.W., Tarnopolsky, M.A. and Phillips, S.M., 2009. Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men. Journal of applied physiology. 107(3), pp. 987-992

9 – Yang, Y., Churchward-Venne, T.A., Burd, N.A., Breen, L., Tarnopolsky, M.A. and Phillips, S.M., 2012. Myofibrillar protein synthesis following ingestion of soy protein isolate at rest and after resistance exercise in elderly men. Nutrition & metabolism, 9(1), pp.1-9.

10 – Deane, C.S., Bass, J.J., Crossland, H., Phillips, B.E. and Atherton, P.J., 2020. Animal, plant, collagen and blended dietary proteins: effects on musculoskeletal outcomes. Nutrients, 12(9), p.2670.

11 – Gorissen, S.H., Horstman, A.M., Franssen, R., Crombag, J.J., Langer, H., Bierau, J., Respondek, F. and Van Loon, L.J., 2016. Ingestion of wheat protein increases in vivo muscle protein synthesis rates in healthy older men in a randomized trial. The Journal of nutrition, 146(9), pp.1651-1659.

12 – Reidy, P.T., Walker, D.K., Dickinson, J.M., Gundermann, D.M., Drummond, M.J., Timmerman, K.L., Fry, C.S., Borack, M.S., Cope, M.B., Mukherjea, R. and Jennings, K., 2013. Protein blend ingestion following resistance exercise promotes human muscle protein synthesis. The Journal of nutrition, 143(4), pp.410-416.

13 – Borack, M.S., Reidy, P.T., Husaini, S.H., Markofski, M.M., Deer, R.R., Richison, A.B., Lambert, B.S., Cope, M.B., Mukherjea, R., Jennings, K. and Volpi, E., 2016. Soy-dairy protein blend or whey protein isolate ingestion induces similar postexercise muscle mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling and protein synthesis responses in older men. The Journal of nutrition, 146(12), pp.2468-2475.

14 – Banaszek, A., Townsend, J.R., Bender, D., Vantrease, W.C., Marshall, A.C. and Johnson, K.D., 2019. The effects of whey vs. pea protein on physical adaptations following 8-weeks of high-intensity functional training (HIFT): A pilot study. Sports, 7(1), p.12.